At first I wasn’t quite sure, when I started reading Dunger. It is a story told in two voices. There is 11 year old Will, and there is his 14 year old sister, Melissa. Like any brother and sister worth their salt, they argue – a lot! Will is a bit of a brain, and enjoys using big words, whereas Melissa has three brain cells. One for fashion, one for boys and one for texting all of her friends who also have only three brain cells. Obviously this is Will’s perspective on the issue, and he doesn’t mince words:

‘The world is full of calamity: famines and wars, birds choking to death on oil spills, earthquakes, tsunamis, and Melissa – my disaster of a sister. Reading this, you’ll probably say, what’s wrong with this kid? Is he a bit paranoid? My response is that all tragedies are relative to their context and as far as domestic upheavals go, this one is about eight on the Richter scale.’

I’ve had to work hard to get my young Des Hunt fan to move beyond that, I can tell you. In fact, the first time I read it, I put the book down, poured myself a wine, and wondered what I should read next.

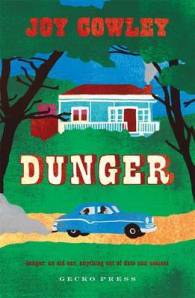

Perhaps I just wasn’t in the right place for a clever, challenging 11 year old demanding my attention…because it’s worth persisting. It really is. I think ‘Dunger’ could well be a great class read aloud, and I’m going to try it out. The writing is sensational because it has an ease to it, as well as a truth and simplicity. And there is plenty of room for fun with characterisations, if you’re going to read it aloud. I can’t help thinking that the grandparent characters are some of the best grandparents I’ve read: funny, grumpy, wise and a little bit dangerous and unpredictable.

Will and Melissa are slightly conned by their parents into staying with their grandparents at the bach. This is a real Kiwi bach, the like of which very few exist anymore. We’re talking no electricity, no shops, postal services twice a week, no cell phone reception and a long drop, complete with possums and spiders, out the back. They are two and a half hours away from the closest town.

The track takes us down to the edge of a bay that is half in sunlight and half in dark shadow. On the shadowed side there’s a stand of old macrocarpa trees. Grandpa pulls over and stops. Neither he nor Grandma says a word.

‘Are we here?’ I ask.

I already know it. Inside the circle of trees is a wooden hut with a brick chimney, a verandah, a water tank and a corrugated iron garage. The grass and scrub around them have grown almost as high as the hut’s windows.

This is the famous bach of my father’s childhood.

It’s a bit much for these two modern young things. But with good old hard work, no useless praise, bread baking, recipes that remind me of my mother’s (how much? A slosh. What’s a slosh? You know, when it looks right. What does right look like?) fishing and swimming, they start to learn a few life lessons. And a more generational perspective of their family.

Grandpa says his grandfather was only the second man in town to own a car, a Buick, he says, shiny black with big running boards and velvet seats, really posh except that he was accustomed to his horse and cart. So when Grandpa’s grandfather drove to church with the family he forgot it was an automobile he was driving, and to stop it he called out, “Whoa! Whoa!” and pulled on the steering wheel. The Buick stopped alright, halfway through the wall of the shop next to the church.

“Does Dad know that story?” I ask.

“Yep, he’s heard it.”

”Why hasn’t he ever told it to us?”

“People remember what they need to remember,” says Grandpa, rubbing his chin exactly the way Dad does. “The rest slips through, which is just as well or our brains would self-destruct. Your Dad was always quiet. Me and your grandma wanted a whole heap of kids but we just got this one boy, kind of gentle, always thinking. Don’t know where he got that from.”

I’m about to agree with him but I’m not sure how he’ll take it, so I just nod. Besides, I wish he’d say more about the flattened grass that looks like newly cut hay.

Their grandparents are just as good at bickering as they are, which Will and Melissa find uncomfortable.

‘I never said there were sharks!” she glares at Grandpa. “He probably told you. Silly old fool, he’ll say anything for a laugh.”

“Be blowed if I did!” he said.

“Be blowed if you didn’t,” she replied.

He leaned over the table towards her. “Woman, you’ve got a tongue in you so long, the back doesn’t know what the front is up to.”

I look at Will who shuts his mouth tight, glaring at me to remind me that I’ve started one of their useless arguments.

And this is one of the real strengths of the book. One of the reasons it’s worth a read. However, rather suddenly, something happens which means everybody needs to work together to prevent disaster.

‘Dunger’ is a satisfying read. It’s impossible to read without bringing to mind ‘Bow Down Shadrach’, since there are elements that are very similar: Marlborough Sounds, parents glossing over truths, adventure and mayhem. My initial reaction was that I enjoyed ‘Bow Down Shadrach’ more, but ‘Dunger’ does have lovely moments, I suspect especially for the parents, or indeed grandparents, of the target readers. However, the subtle strength of this book is how enduringly it has stayed with me. The characters are vivid and real, and the Marlborough Sounds setting is so well drawn I feel as though I visited and remember the bach, rather than read about it. In the end, it doesn’t matter which is the better, since I think both are an important part of the New Zealand Children’s Literature landscape.

Read other reviews here: